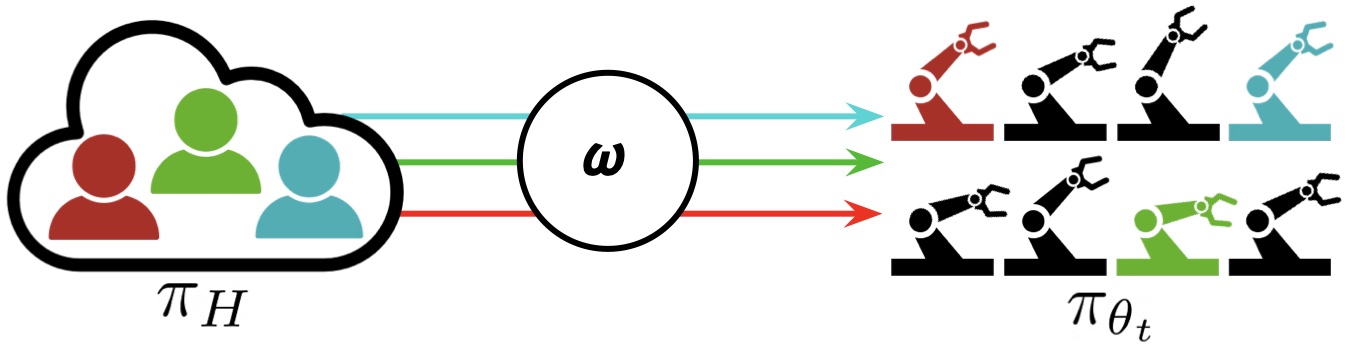

Figure 1: “Interactive Fleet Learning” (IFL) refers to robot fleets in industry and academia that fall back on human teleoperators when necessary and continually learn from them over time.

In the last few years we have seen an exciting development in robotics and artificial intelligence: large fleets of robots have left the lab and entered the real world. Waymo, for example, has over 700 self-driving cars operating in Phoenix and San Francisco and is currently expanding to Los Angeles. Other industrial deployments of robot fleets include applications like e-commerce order fulfillment at Amazon and Ambi Robotics as well as food delivery at Nuro and Kiwibot.

Commercial and industrial deployments of robot fleets: package delivery (top left), food delivery (bottom left), e-commerce order fulfillment at Ambi Robotics (top right), autonomous taxis at Waymo (bottom right).

These robots use recent advances in deep learning to operate autonomously in unstructured environments. By pooling data from all robots in the fleet, the entire fleet can efficiently learn from the experience of each individual robot. Furthermore, due to advances in cloud robotics, the fleet can offload data, memory, and computation (e.g., training of large models) to the cloud via the Internet. This approach is known as “Fleet Learning,” a term popularized by Elon Musk in 2016 press releases about Tesla Autopilot and used in press communications by Toyota Research Institute, Wayve AI, and others. A robot fleet is a modern analogue of a fleet of ships, where the word fleet has an etymology tracing back to flēot (‘ship’) and flēotan (‘float’) in Old English.

Data-driven approaches like fleet learning, however, face the problem of the “long tail”: the robots inevitably encounter new scenarios and edge cases that are not represented in the dataset. Naturally, we can’t expect the future to be the same as the past! How, then, can these robotics companies ensure sufficient reliability for their services?

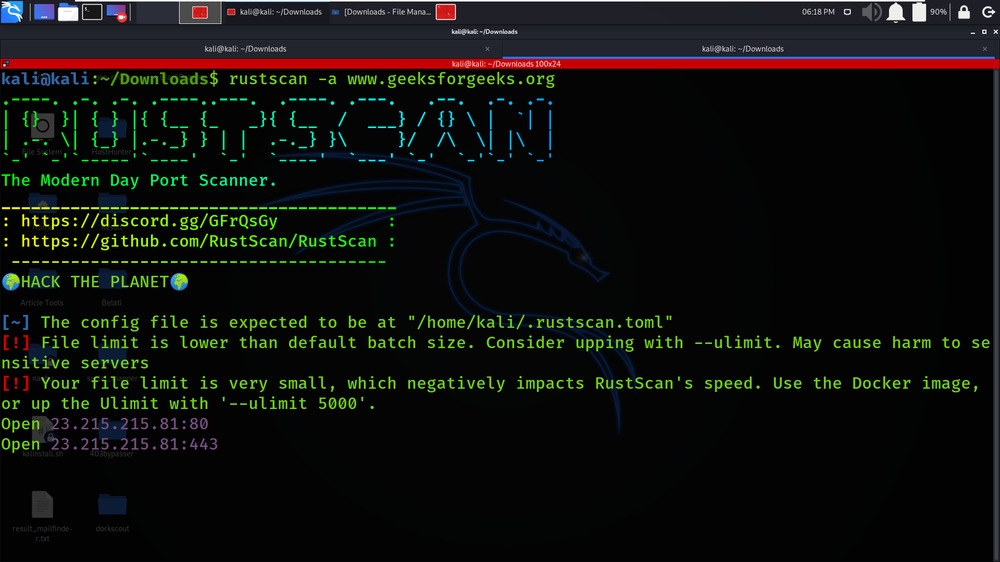

One answer is to fall back on remote humans over the Internet, who can interactively take control and “tele-operate” the system when the robot policy is unreliable during task execution. Teleoperation has a rich history in robotics: the world’s first robots were teleoperated during WWII to handle radioactive materials, and the Telegarden pioneered robot control over the Internet in 1994. With continual learning, the human teleoperation data from these interventions can iteratively improve the robot policy and reduce the robots’ reliance on their human supervisors over time. Rather than a discrete jump to full robot autonomy, this strategy offers a continuous alternative that approaches full autonomy over time while simultaneously enabling reliability in robot systems today.

The use of human teleoperation as a fallback mechanism is increasingly popular in modern robotics companies: Waymo calls it “fleet response,” Zoox calls it “TeleGuidance,” and Amazon calls it “continual learning.” Last year, a software platform for remote driving called Phantom Auto was recognized by Time Magazine as one of their Top 10 Inventions of 2022. And just last month, John Deere acquired SparkAI, a startup that develops software for resolving edge cases with humans in the loop.

A remote human teleoperator at Phantom Auto, a software platform for enabling remote driving over the Internet.

Despite this growing trend in industry, however, there has been comparatively little focus on this topic in academia. As a result, robotics companies have had to rely on ad hoc solutions for determining when their robots should cede control. The closest analogue in academia is interactive imitation learning (IIL), a paradigm in which a robot intermittently cedes control to a human supervisor and learns from these interventions over time. There have been a number of IIL algorithms in recent years for the single-robot, single-human setting including DAgger and variants such as HG-DAgger, SafeDAgger, EnsembleDAgger, and ThriftyDAgger; nevertheless, when and how to switch between robot and human control is still an open problem. This is even less understood when the notion is generalized to robot fleets, with multiple robots and multiple human supervisors.

IFL Formalism and Algorithms

To this end, in a recent paper at the Conference on Robot Learning we introduced the paradigm of Interactive Fleet Learning (IFL), the first formalism in the literature for interactive learning with multiple robots and multiple humans. As we’ve seen that this phenomenon already occurs in industry, we can now use the phrase “interactive fleet learning” as unified terminology for robot fleet learning that falls back on human control, rather than keep track of the names of every individual corporate solution (“fleet response”, “TeleGuidance”, etc.). IFL scales up robot learning with four key components:

- On-demand supervision. Since humans cannot effectively monitor the execution of multiple robots at once and are prone to fatigue, the allocation of robots to humans in IFL is automated by some allocation policy $\omega$. Supervision is requested “on-demand” by the robots rather than placing the burden of continuous monitoring on the humans.

- Fleet supervision. On-demand supervision enables effective allocation of limited human attention to large robot fleets. IFL allows the number of robots to significantly exceed the number of humans (e.g., by a factor of 10:1 or more).

- Continual learning. Each robot in the fleet can learn from its own mistakes as well as the mistakes of the other robots, allowing the amount of required human supervision to taper off over time.

- The Internet. Thanks to mature and ever-improving Internet technology, the human supervisors do not need to be physically present. Modern computer networks enable real-time remote teleoperation at vast distances.

In the Interactive Fleet Learning (IFL) paradigm, M humans are allocated to the robots that need the most help in a fleet of N robots (where N can be much larger than M). The robots share policy $\pi_{\theta_t}$ and learn from human interventions over time.

We assume that the robots share a common control policy $\pi_{\theta_t}$ and that the humans share a common control policy $\pi_H$. We also assume that the robots operate in independent environments with identical state and action spaces (but not identical states). Unlike a robot swarm of typically low-cost robots that coordinate to achieve a common objective in a shared environment, a robot fleet simultaneously executes a shared policy in distinct parallel environments (e.g., different bins on an assembly line).

The goal in IFL is to find an optimal supervisor allocation policy $\omega$, a mapping from $\mathbf{s}^t$ (the state of all robots at time t) and the shared policy $\pi_{\theta_t}$ to a binary matrix that indicates which human will be assigned to which robot at time t. The IFL objective is a novel metric we call the “return on human effort” (ROHE):

\[\max_{\omega \in \Omega} \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim p_{\omega, \theta_0}(\tau)} \left[\frac{M}{N} \cdot \frac{\sum_{t=0}^T \bar{r}( \mathbf{s}^t, \mathbf{a}^t)}{1+\sum_{t=0}^T \|\omega(\mathbf{s}^t, \pi_{\theta_t}, \cdot) \|^2 _F} \right]\]

where the numerator is the total reward across robots and timesteps and the denominator is the total amount of human actions across robots and timesteps. Intuitively, the ROHE measures the performance of the fleet normalized by the total human supervision required. See the paper for more of the mathematical details.

Using this formalism, we can now instantiate and compare IFL algorithms (i.e., allocation policies) in a principled way. We propose a family of IFL algorithms called Fleet-DAgger, where the policy learning algorithm is interactive imitation learning and each Fleet-DAgger algorithm is parameterized by a unique priority function $\hat p: (s, \pi_{\theta_t}) \rightarrow [0, \infty)$ that each robot in the fleet uses to assign itself a priority score. Similar to scheduling theory, higher priority robots are more likely to receive human attention. Fleet-DAgger is general enough to model a wide range of IFL algorithms, including IFL adaptations of existing single-robot, single-human IIL algorithms such as EnsembleDAgger and ThriftyDAgger. Note, however, that the IFL formalism isn’t limited to Fleet-DAgger: policy learning could be performed with a reinforcement learning algorithm like PPO, for instance.

IFL Benchmark and Experiments

To determine how to best allocate limited human attention to large robot fleets, we need to be able to empirically evaluate and compare different IFL algorithms. To this end, we introduce the IFL Benchmark, an open-source Python toolkit available on Github to facilitate the development and standardized evaluation of new IFL algorithms. We extend NVIDIA Isaac Gym, a highly optimized software library for end-to-end GPU-accelerated robot learning released in 2021, without which the simulation of hundreds or thousands of learning robots would be computationally intractable. Using the IFL Benchmark, we run large-scale simulation experiments with N = 100 robots, M = 10 algorithmic humans, 5 IFL algorithms, and 3 high-dimensional continuous control environments (Figure 1, left).

We also evaluate IFL algorithms in a real-world image-based block pushing task with N = 4 robot arms and M = 2 remote human teleoperators (Figure 1, right). The 4 arms belong to 2 bimanual ABB YuMi robots operating simultaneously in 2 separate labs about 1 kilometer apart, and remote humans in a third physical location perform teleoperation through a keyboard interface when requested. Each robot pushes a cube toward a unique goal position randomly sampled in the workspace; the goals are programmatically generated in the robots’ overhead image observations and automatically resampled when the previous goals are reached. Physical experiment results suggest trends that are approximately consistent with those observed in the benchmark environments.

Takeaways and Future Directions

To address the gap between the theory and practice of robot fleet learning as well as facilitate future research, we introduce new formalisms, algorithms, and benchmarks for Interactive Fleet Learning. Since IFL does not dictate a specific form or architecture for the shared robot control policy, it can be flexibly synthesized with other promising research directions. For instance, diffusion policies, recently demonstrated to gracefully handle multimodal data, can be used in IFL to allow heterogeneous human supervisor policies. Alternatively, multi-task language-conditioned Transformers like RT-1 and PerAct can be effective “data sponges” that enable the robots in the fleet to perform heterogeneous tasks despite sharing a single policy. The systems aspect of IFL is another compelling research direction: recent developments in cloud and fog robotics enable robot fleets to offload all supervisor allocation, model training, and crowdsourced teleoperation to centralized servers in the cloud with minimal network latency.

While Moravec’s Paradox has so far prevented robotics and embodied AI from fully enjoying the recent spectacular success that Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 have demonstrated, the “bitter lesson” of LLMs is that supervised learning at unprecedented scale is what ultimately leads to the emergent properties we observe. Since we don’t yet have a supply of robot control data nearly as plentiful as all the text and image data on the Internet, the IFL paradigm offers one path forward for scaling up supervised robot learning and deploying robot fleets reliably in today’s world.

Acknowledgements

This post is based on the paper “Fleet-DAgger: Interactive Robot Fleet Learning with Scalable Human Supervision” presented at the 6th Annual Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL) in December 2022 in Auckland, New Zealand. The research was performed at the AUTOLab at UC Berkeley in affiliation with the Berkeley AI Research (BAIR) Lab and the CITRIS “People and Robots” (CPAR) Initiative. The authors were supported in part by donations from Google, Siemens, Toyota Research Institute, and Autodesk and by equipment grants from PhotoNeo, NVidia, and Intuitive Surgical. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors. Thanks to co-authors Lawrence Chen, Satvik Sharma, Karthik Dharmarajan, Brijen Thananjeyan, Pieter Abbeel, and Ken Goldberg for their contributions and helpful feedback on this work.

For more details on interactive fleet learning, see the paper on arXiv, CoRL presentation video on YouTube, open-source codebase on Github, high-level summary on Twitter, and project website.

If you would like to cite this article, please use the following bibtex:

@article{ifl_blog,

title={Interactive Fleet Learning},

author={Hoque, Ryan},

url={https://bair.berkeley.edu/blog/2023/04/06/ifl/},

journal={Berkeley Artificial Intelligence Research Blog},

year={2023}

}