Reverse-Engineering YouTube: Revisited • Oleksii Holub

Back in 2017 I wrote an article in which I attempted to explain how YouTube works under the hood, how it serves streams to the client, and also how you can exploit that knowledge to download videos from the site. The primary goal of that write-up was to share what I learned while working on YoutubeExplode — a .NET library that provides a structured abstraction layer over YouTube’s internal API.

There is one thing that developers like more than building things — and that is breaking things built by other people. So, naturally, my article attracted quite a bit of attention and still remains one of the most popular posts on this blog. In any case, I really enjoyed doing the research, and I’m glad that it was also useful to other people.

However, a lot has changed in the five years since the article was published: YouTube has evolved as a platform, went through multiple UI redesigns, and completely overhauled its frontend codebase. Most of the internal endpoints that were reverse-engineered in the early days have been gradually getting removed altogether. In fact, nearly everything covered in the original post has become obsolete and now only serves as a historical reference.

I know that there’s still plenty of interest around this topic, so I’ve been meaning to revisit it and make a follow-up article with new and updated information. Seeing as YouTube has once again entered a quiet phase in terms of change and innovation, I figured that now is finally a good time to do it.

In this article, I’ll cover the current state of YouTube’s internal API, highlight the most important changes, and explain how things work today. Just like before, I will focus on the video playback aspect of the platform, outlining everything you need to do in order to resolve video streams and download them.

Retrieving the metadata

If you’ve worked with YouTube in the past, you’ll probably remember /get_video_info. This internal API controller was used throughout YouTube’s client code to retrieve video metadata, available streams, and any other information needed to render the player. The origin of this endpoint traces back to the Flash Player days of YouTube, and it was still accessible until as late as July 2021, before it was finally removed.

Besides /get_video_info, YouTube has also dropped many other endpoints, such as /get_video_metadata (in November 2017) and /list_ajax (in February 2021), as part of a larger effort to establish a more organized API structure. Now, instead of having a bunch of randomly scattered endpoints with unpredictable formats and usage patterns, YouTube’s internal API is comprised out of a coherent set of routes nested underneath the /youtubei/ path.

In particular, much of the data previously obtainable from /get_video_info can now be pulled using the /youtubei/v1/player route. Unlike its predecessor, this endpoint expects a POST request — and the payload looks like this:

// POST https://www.youtube.com/youtubei/v1/player?key=AIzaSyA8eiZmM1FaDVjRy-df2KTyQ_vz_yYM39w

{

"videoId": "e_S9VvJM1PI",

"context": {

"client": {

"clientName": "ANDROID",

"clientVersion": "17.10.35",

"androidSdkVersion": 30

}

}

}

First thing you’ll notice is that this endpoint requires an API key, which is passed through the key parameter in the URL. Each YouTube client has its own key assigned to it, but the endpoint doesn’t actually care which one is used as long as it’s valid. Because the keys don’t rotate either, it’s safe to pick one and hard code it as part of the URL.

The request body itself is a JSON object with two top-level properties: videoId and context. The former is the 11-character ID of the video you want to retrieve the metadata for, while the latter contains various information that YouTube uses to tailor the response to the client’s preferences and capabilities.

In particular, depending on the client you choose to impersonate using the clientName and clientVersion properties, the response may contain slightly different data, or just fail to resolve altogether for certain videos. While there are many clients available, only a few of them provide a measurable advantage over the others — which is why ANDROID, being the easiest work with, is used in the example above.

After receiving the response, you should find a JSON object that contains the video metadata, stream descriptors, closed captions, activity tracking URLs, ad placements, post-playback screen elements — basically everything that the client needs in order to show the video to the user. It’s a massive blob of data, so to make things simpler I’ve outlined only the most interesting parts below:

{

"videoDetails": {

"videoId": "e_S9VvJM1PI",

"title": "Icon For Hire - Make A Move",

"lengthSeconds": "184",

"keywords": ["Icon", "For", "Hire", "Make", "Move", "Tooth", "Nail", "(TNN)", "Rock"],

"channelId": "UCKvT-8xU_BTJGvsQ5lR23TQ",

"isOwnerViewing": false,

"shortDescription": "Music video by Icon For Hire performing Make A Move. (P) (C) 2011 Tooth & Nail Records. All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction is a violation of applicable laws. Manufactured by Tooth & Nail,\n\n#IconForHire #MakeAMove #Vevo #Rock #VevoOfficial #OfficialMusicVideo",

"isCrawlable": true,

"thumbnail": {

"thumbnails": [

{

"url": "https://i.ytimg.com/vi/e_S9VvJM1PI/default.jpg",

"width": 120,

"height": 90

},

{

"url": "https://i.ytimg.com/vi/e_S9VvJM1PI/mqdefault.jpg",

"width": 320,

"height": 180

},

{

"url": "https://i.ytimg.com/vi/e_S9VvJM1PI/hqdefault.jpg",

"width": 480,

"height": 360

},

{

"url": "https://i.ytimg.com/vi/e_S9VvJM1PI/sddefault.jpg",

"width": 640,

"height": 480

}

]

},

"allowRatings": true,

"viewCount": "54284943",

"author": "IconForHireVEVO",

"isPrivate": false,

"isUnpluggedCorpus": false,

"isLiveContent": false

},

"playabilityStatus": {

"status": "OK",

"playableInEmbed": true

},

"streamingData": {

"expiresInSeconds": "21540",

"formats": [

/* ... */

],

"adaptiveFormats": [

/* ... */

]

}

/* ... omitted ~1800 lines of irrelevant data ... */

}

As you can immediately see, the response contains a range of useful information. From videoDetails, you can extract the video title, duration, author, view count, thumbnails, and other relevant metadata. This includes most of the stuff you will find on the video page, with the exception of likes, dislikes, channel subscribers, and other bits that are not rendered directly by the player.

Next, the playabilityStatus object indicates whether the video is playable within the context of the client that made the request. In case it’s not, a reason property will be included with a human-readable message explaining why — for example, because the video is intended for mature audiences, or because it’s not accessible in the current region. When dealing with unplayable videos, you’ll still be able to obtain their metadata, but you won’t be able to retrieve any streams.

Finally, assuming the video is marked as playable, streamingData should contain the list of streams that YouTube provided for the playback. These are divided into the formats and adaptiveFormats arrays inside the response, and correspond to the various quality options available in the player.

The separation between formats and adaptiveFormats is a bit confusing and I found that it doesn’t refer so much to the delivery method, but rather to the way the streams are encoded. Specifically, the formats array describes traditional video streams, where both the audio and the video tracks are combined into a single container ahead of time, while adaptiveFormats lists dedicated audio-only and video-only streams, which are overlaid at run-time by the player.

You’ll find that most of the playback options, especially the higher-fidelity ones, are provided using the latter approach, because it’s more flexible in terms of bandwidth. By being able to switch the audio and video streams independently, the player can adapt to varying network conditions, as well as different playback contexts — for example, by requesting only the audio stream if the user is consuming content from YouTube Music.

As far as the metadata is concerned, both arrays are very similar and contain objects with the following structure:

{

"itag": 18,

"url": "https://rr12---sn-3c27sn7d.googlevideo.com/videoplayback?expire=1669027268&ei=ZAF7Y8WaA4i3yQWsxLyYDw&ip=111.111.111.111&id=o-AC63-WVHdIW_Ueyvj6ZZ1eC3oHHyfY14KZOpHNncjXa4&itag=18&source=youtube&requiressl=yes&mh=Qv&mm=31%2C26&mn=sn-3c27sn7d%2Csn-f5f7lnld&ms=au%2Conr&mv=m&mvi=12&pl=24&gcr=ua&initcwndbps=1521250&vprv=1&svpuc=1&xtags=heaudio%3Dtrue&mime=video%2Fmp4&cnr=14&ratebypass=yes&dur=183.994&lmt=1665725827618480&mt=1669005418&fvip=1&fexp=24001373%2C24007246&c=ANDROID&txp=5538434&sparams=expire%2Cei%2Cip%2Cid%2Citag%2Csource%2Crequiressl%2Cgcr%2Cvprv%2Csvpuc%2Cxtags%2Cmime%2Ccnr%2Cratebypass%2Cdur%2Clmt&sig=AOq0QJ8wRQIge8aU9csL5Od685kA1to0PB6ggVeuLJjfSfTpZVsgEToCIQDZEk4dQyXJViNJr9EyGUhecGCk2RCFzXIJAZuuId4Bug%3D%3D&lsparams=mh%2Cmm%2Cmn%2Cms%2Cmv%2Cmvi%2Cpl%2Cinitcwndbps&lsig=AG3C_xAwRgIhAP5rrAq5OoZ0e5bgNZpztkbKGgayb-tAfBbM3Z4VrpDfAiEAkcg66j1nSan1vbvg79sZJkJMMFv1jb2tDR_Z7kS2z9M%3D",

"mimeType": "video/mp4; codecs=\"avc1.42001E, mp4a.40.2\"",

"lastModified": "1665725827618480",

"approxDurationMs": "183994",

"bitrate": 503351,

"width": 640,

"height": 360,

"projectionType": "RECTANGULAR",

"fps": 30,

"quality": "medium",

"qualityLabel": "360p",

"audioQuality": "AUDIO_QUALITY_LOW",

"audioSampleRate": "22050",

"audioChannels": 2

}

Most of the properties here are fairly self-explanatory as they detail the format and overall quality of the stream. For example, from the information above you can tell that this is a muxed (i.e. audio and video combined) mp4 stream, encoded using the H.264 video codec and AAC audio codec, with a resolution of 640x360 pixels, 30 frames per second, and a bitrate of 503 kbps. If played on YouTube, this stream would be available as the 360p quality option.

Each stream is also uniquely identified by something called an itag, which is a numeric code that refers to the encoding preset used internally by YouTube to transform the source media into a given representation. In the past, this value was the most reliable way to determine the exact encoding parameters of a particular stream, but the new response has enough metadata to make this approach redundant.

Of course, the most interesting part of the entire object is the url property. This is the URL that you can use to fetch the actual binary stream data, either by sending a GET request or by opening it in a browser:

Note that if you try to open the URL from the JSON snippet shown above, you’ll get a 403 Forbidden error. That’s because YouTube stream URLs are not static — they are generated individually for each client and have a fixed expiration time. Once the stream manifest is resolved, the URLs inside it stay valid for only 6 hours and cannot be accessed from a different IP address.

You can confirm this by looking at the ip and expire query parameters in the URL, which contain the client’s IP address and the expiration timestamp respectively. While it may be tempting, these values cannot be changed manually to lift these limitations, because their integrity is protected by a special parameter called sig. Trying to change any of the parameters listed inside sparams, without correctly updating the signature, will result in a 403 Forbidden error as well.

In any case, the steps outlined so far should be enough to resolve and download streams for most YouTube videos. However, some videos may require a bit of extra work, which is what we’re going to cover in the next section.

Working around content restrictions

YouTube has an extensive content moderation system, so you may occasionally encounter videos that cannot be played and, thus, downloaded. The two most common reasons for that are:

- The video is blocked in your country, because it features content that the uploader has not licensed for use in your region

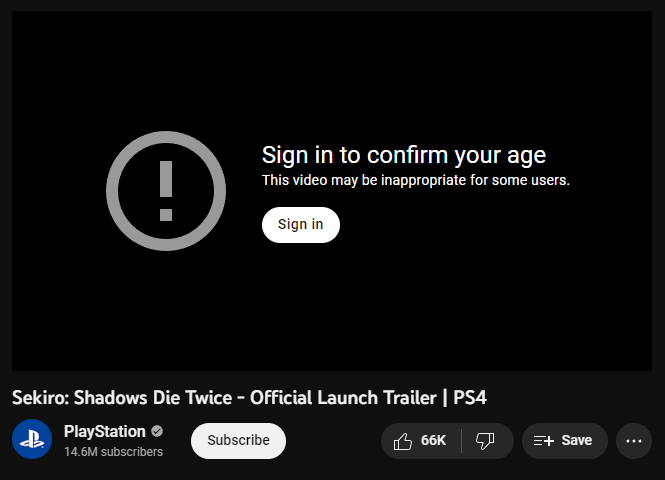

- The video is age-gated, because it features content that is not suitable for minors, as determined by YouTube or the uploader themselves

The way region-based restrictions work is fairly straightforward — YouTube identifies whether your IP address maps to one of the blocked countries and prohibits access to the video if that’s the case. There is not much that can be done about it, other than using a VPN to spoof the device’s location.

For age-based restrictions, on the other hand, YouTube does not infer any information from the client, but rather relies on the user’s consent. To provide it, the user is required to sign in to their account and confirm that they are 18 years or older:

While it is possible to simulate the same flow programmatically — by authenticating on the user’s behalf and then passing cookies to the /youtubei/v1/player endpoint — the process is very cumbersome and error-prone. Luckily, there is a way to bypass this restriction altogether.

As it turns out, there is one obscure YouTube client that lets you access age-gated videos completely unauthenticated, and that’s the embedded player used for Smart TV browsers. This means that if you impersonate this client in the initial request, you can get working stream manifests for age-restricted videos, without worrying about cookies or user credentials. To do that, update the request body as follows:

// POST https://www.youtube.com/youtubei/v1/player?key=AIzaSyA8eiZmM1FaDVjRy-df2KTyQ_vz_yYM39w

{

"videoId": "e_S9VvJM1PI",

"context": {

"client": {

"clientName": "TVHTML5_SIMPLY_EMBEDDED_PLAYER",

"clientVersion": "2.0"

},

"thirdParty": {

"embedUrl": "https://www.youtube.com"

}

}

}

The main difference from the ANDROID client is that TVHTML5_SIMPLY_EMBEDDED_PLAYER also supports a thirdParty object that contains the URL of the page where the video is supposedly embedded. While it’s not strictly required to include this parameter, specifying https://www.youtube.com allows the request to succeed even for videos that prohibit embedding on third-party websites.

One significant drawback of impersonating this client, however, is that it does not represent a native app like ANDROID, but rather a JavaScript-based player that runs in the browser. This type of client is susceptible to an additional security measure used by YouTube, which obfuscates the URLs contained within the stream metadata. Here is how an individual stream descriptor looks in that case:

{

"itag": 18,

"signatureCipher": "s=CC%3DQ8o2zpxwirVyNq_miGGr282CaNsFfzUBBPgQU-8sKj2BiANNbb7LJ8ukTN%3DNAn-PJD-m57czWRI1DsA6uqrtC0slMAhIQRw8JQ0qOTT&sp=sig&url=https://rr12---sn-3c27sn7d.googlevideo.com/videoplayback%3Fexpire%3D1674722398%26ei%3D_ufRY5XOJsnoyQWFno_IBg%26ip%3D111.111.111.111%26id%3Do-AGdzTbHeYCSShTUoAvdKXasA0mPM9YKXx5XP2lYQDkgI%26itag%3D18%26source%3Dyoutube%26requiressl%3Dyes%26mh%3DQv%26mm%3D31%252C26%26mn%3Dsn-3c27sn7d%252Csn-f5f7lnld%26ms%3Dau%252Conr%26mv%3Dm%26mvi%3D12%26pl%3D24%26gcr%3Dua%26initcwndbps%3D2188750%26vprv%3D1%26xtags%3Dheaudio%253Dtrue%26mime%3Dvideo%252Fmp4%26ns%3DiTmK1jXtWdMktMzKoaHSpR4L%26cnr%3D14%26ratebypass%3Dyes%26dur%3D183.994%26lmt%3D1665725827618480%26mt%3D1674700623%26fvip%3D1%26fexp%3D24007246%26c%3DTVHTML5_SIMPLY_EMBEDDED_PLAYER%26txp%3D5538434%26n%3DMzirMb1rQM4r8h6gw%26sparams%3Dexpire%252Cei%252Cip%252Cid%252Citag%252Csource%252Crequiressl%252Cgcr%252Cvprv%252Cxtags%252Cmime%252Cns%252Ccnr%252Cratebypass%252Cdur%252Clmt%26lsparams%3Dmh%252Cmm%252Cmn%252Cms%252Cmv%252Cmvi%252Cpl%252Cinitcwndbps%26lsig%3DAG3C_xAwRQIgXGtBJv7BPshy6oDP4ghnH1Fhq_AFSAZAcwYs93fbYVMCIQDC-RKyYocOttpdf9_X_98thhRLy2TaKDvjgrg8fQtw7w%253D%253D",

"mimeType": "video/mp4; codecs=\"avc1.42001E, mp4a.40.2\"",

"lastModified": "1665725827618480",

"xtags": "Cg8KB2hlYXVkaW8SBHRydWU",

"approxDurationMs": "183994",

"bitrate": 503351,

"width": 640,

"height": 360,

"projectionType": "RECTANGULAR",

"fps": 30,

"quality": "medium",

"qualityLabel": "360p",

"audioQuality": "AUDIO_QUALITY_LOW",

"audioSampleRate": "22050",

"audioChannels": 2

}

Although the structure is mostly identical to the example from earlier, you will find that the url property is absent from the metadata. Instead, it’s replaced by signatureCipher — a URL-encoded dictionary that contains the following key-value pairs:

s=CC=Q8o2zpxwirVyNq_miGGr282CaNsFfzUBBPgQU-8sKj2BiANNbb7LJ8ukTN=NAn-PJD-m57czWRI1DsA6uqrtC0slMAhIQRw8JQ0qOTT

sp=sig

url=https://rr12---sn-3c27sn7d.googlevideo.com/videoplayback?expire=1674722398&ei=_ufRY5XOJsnoyQWFno_IBg&ip=111.111.111.111&id=o-AGdzTbHeYCSShTUoAvdKXasA0mPM9YKXx5XP2lYQDkgI&itag=18&source=youtube&requiressl=yes&mh=Qv&mm=31%2C26&mn=sn-3c27sn7d%2Csn-f5f7lnld&ms=au%2Conr&mv=m&mvi=12&pl=24&gcr=ua&initcwndbps=2188750&vprv=1&xtags=heaudio%3Dtrue&mime=video%2Fmp4&ns=iTmK1jXtWdMktMzKoaHSpR4L&cnr=14&ratebypass=yes&dur=183.994&lmt=1665725827618480&mt=1674700623&fvip=1&fexp=24007246&c=TVHTML5_SIMPLY_EMBEDDED_PLAYER&txp=5538434&n=MzirMb1rQM4r8h6gw&sparams=expire%2Cei%2Cip%2Cid%2Citag%2Csource%2Crequiressl%2Cgcr%2Cvprv%2Cxtags%2Cmime%2Cns%2Ccnr%2Cratebypass%2Cdur%2Clmt&lsparams=mh%2Cmm%2Cmn%2Cms%2Cmv%2Cmvi%2Cpl%2Cinitcwndbps&lsig=AG3C_xAwRQIgXGtBJv7BPshy6oDP4ghnH1Fhq_AFSAZAcwYs93fbYVMCIQDC-RKyYocOttpdf9_X_98thhRLy2TaKDvjgrg8fQtw7w%3D%3D

Here, the provided url value is the base part of the stream URL, but it’s missing an important element — the signature string. In order to obtain the correct link, you need to recover the signature from the s value and append it back to the base URL as a query parameter identified by sp. The challenge, however, is that the signature is encoded with a special cipher, meaning that you need to decipher it before you can use it.

Normally, when running in the browser, the deciphering process is performed by the player itself, using the instructions stored within it. The exact set of cipher operations and their order changes with each version, so the only way to reproduce this process programmatically is by downloading the player’s source code and extracting the implementation from there.

To do that, you need to first identify the latest version of the player, which can be done by querying the /iframe_api endpoint. It’s the same endpoint that YouTube uses for embedding videos on third-party websites, and it returns a script file that looks like this:

var scriptUrl = 'https://www.youtube.com/s/player/4248d311/www-widgetapi.vflset/www-widgetapi.js';

/* ... omitted ~40 lines of irrelevant code ... */

Within it, you will find a variable named scriptUrl that references one of the player’s JavaScript assets. While this URL is not particularly useful on its own, it does include the player version inside, which is 4248d311 in this case. Having obtained that, you can download the player’s source code by substituting the version into the template below:

https://www.youtube.com/s/player/{version}/player_ias.vflset/en_US/base.js

Even though the source file is a massive blob of minified, unreadable JavaScript code, locating the deciphering instructions is fairly simple. All you need to do is search for a=a.split("");, which should bring you to the entry step of the deciphering process. For the above player version, it looks like this:

// Prettified for readability

fta = function (a) {

a = a.split('');

hD.mL(a, 79);

hD.L5(a, 2);

hD.mL(a, 24);

hD.L5(a, 3);

return a.join('');

};

As you can see, the deciphering algorithm is implemented as the fta(...) function that takes a single argument (the s value from earlier) and passes it through a series of transforms. The transforms themselves are defined as methods on the hD object located in the same scope:

// Prettified for readability

var hD = {

// Swap transform

i1: function (a, b) {

var c = a[0];

a[0] = a[b % a.length];

a[b % a.length] = c;

},

// Splice transform

L5: function (a, b) {

a.splice(0, b);

},

// Reverse transform

mL: function (a) {

a.reverse();

}

};

Depending on the version of the player, the names of the above objects and functions will be different, but the deciphering algorithm will always be implemented as a randomized sequence of the following operations:

- Swap, which replaces the first character in the string with the character at the specified index

- Splice, which removes the specified number of characters from the beginning of the string

- Reverse, which reverses the order of characters in the string

Looking back at the fta(...) function, we can conclude that this version of the algorithm only relies on the last two operations, and combines them like so:

hD.mL(a): reverses the stringhD.L5(a, 2): removes the first 2 charactershD.mL(a): reverses the string againhD.L5(a, 3): removes the first 3 characters

Before these steps can be applied to recover the stream signature, however, you need to resolve a manifest that’s actually synchronized with the current implementation of the cipher. That’s because there are many versions of the player in use at the same time, so it’s important that the manifest returned by the /youtubei/v1/player endpoint is compatible with the deciphering instructions you’ve extracted.

To identify a particular implementation of the cipher, YouTube does not rely on the player version, but rather on a special value called signatureTimestamp. This value is used as a random seed to generate the cipher algorithm, and to keep it consistent between the client and the server. You can extract it from the player’s source code by searching for signatureTimestamp:

// Prettified for readability

var v = {

splay: !1,

lactMilliseconds: c.LACT.toString(),

playerHeightPixels: Math.trunc(c.P_H),

playerWidthPixels: Math.trunc(c.P_W),

vis: Math.trunc(c.VIS),

// Seed for the cipher algorithm:

signatureTimestamp: 19369,

// -----------------------------

autonavState: MDa(a.player.V())

};

Finally, update the original request to the /youtubei/v1/player endpoint to include the retrieved value inside the JSON payload. Specifically, the timestamp should be passed as part of an additional top-level object called playbackContext:

// POST https://www.youtube.com/youtubei/v1/player?key=AIzaSyA8eiZmM1FaDVjRy-df2KTyQ_vz_yYM39w

{

"videoId": "e_S9VvJM1PI",

"context": {

"client": {

"clientName": "TVHTML5_SIMPLY_EMBEDDED_PLAYER",

"clientVersion": "2.0"

},

"thirdParty": {

"embedUrl": "https://www.youtube.com"

}

},

"playbackContext": {

"contentPlaybackContext": {

"signatureTimestamp": "19369"

}

}

}

With that, the returned stream descriptors should contain matching signature ciphers, allowing you to correctly reconstruct the URLs using the deciphering instructions extracted earlier.

Working around rate limiting

One common issue that you’ll likely encounter is that certain streams might take an abnormally long time to fully download. This is usually caused by YouTube’s rate limiting mechanism, which is designed to prevent excessive bandwidth usage by capping the rate at which the streams are served to the client.

It makes sense from a logical perspective — there is no reason for YouTube to transfer the video faster than it is being played, especially if the user may not decide to watch it all the way through. However, when the goal is to download the content as quickly as possible, it can become a major obstacle.

All YouTube streams are rate-limited by default, but depending on their type and the client you’re impersonating, you may find some that are not. In order to identify whether a particular stream is rate-limited, you can check for the ratebypass query parameter in the URL — if it’s present and set to yes, then the rate limiting is disabled for that stream, and you should be able to fetch it at full speed:

https://rr12---sn-3c27sn7d.googlevideo.com/videoplayback

?expire=1669027268

&ei=ZAF7Y8WaA4i3yQWsxLyYDw

&ip=111.111.111.111

&id=o-AC63-WVHdIW_Ueyvj6ZZ1eC3oHHyfY14KZOpHNncjXa4

&itag=18

&source=youtube

&requiressl=yes

&mh=Qv

&mm=31%2C26

&mn=sn-3c27sn7d%2Csn-f5f7lnld

&ms=au%2Conr

&mv=m

&mvi=12

&pl=24

&gcr=ua

&initcwndbps=1521250

&vprv=1

&svpuc=1

&xtags=heaudio%3Dtrue

&mime=video%2Fmp4

&cnr=14

# Rate limiting is disabled:

&ratebypass=yes

# --------------------------

&dur=183.994

&lmt=1665725827618480

&mt=1669005418

&fvip=1

&fexp=24001373%2C24007246

&c=ANDROID

&txp=5538434

&sparams=expire%2Cei%2Cip%2Cid%2Citag%2Csource%2Crequiressl%2Cgcr%2Cvprv%2Csvpuc%2Cxtags%2Cmime%2Ccnr%2Cratebypass%2Cdur%2Clmt

&sig=AOq0QJ8wRQIge8aU9csL5Od685kA1to0PB6ggVeuLJjfSfTpZVsgEToCIQDZEk4dQyXJViNJr9EyGUhecGCk2RCFzXIJAZuuId4Bug%3D%3D

&lsparams=mh%2Cmm%2Cmn%2Cms%2Cmv%2Cmvi%2Cpl%2Cinitcwndbps

&lsig=AG3C_xAwRgIhAP5rrAq5OoZ0e5bgNZpztkbKGgayb-tAfBbM3Z4VrpDfAiEAkcg66j1nSan1vbvg79sZJkJMMFv1jb2tDR_Z7kS2z9M%3D

Unfortunately, the ratebypass parameter is not always present in the stream URL, and even when it is, it’s not guaranteed to be set to yes. On top of that, as already mentioned before, you can’t simply edit the URL to add the parameter manually, as that would invalidate the signature and render the link unusable.

However, YouTube’s rate limiting has one interesting aspect — it only affects streams whose content length exceeds a certain threshold. This means that if the stream is small enough, the data will be served at maximum speed, regardless of whether the ratebypass parameter is set or not. In my tests, I found that the exact cut-off point seems to be around 10 megabytes, with anything larger than that causing the throttling to kick in.

What makes this behavior more useful is that the threshold doesn’t actually apply to the overall size of the stream, but rather to the size of the requested part. In other words, if you try fetching only a portion of the data — using the Range HTTP header — YouTube will serve the corresponding content at full speed, as long as the specified byte range is smaller than 10 megabytes.

As a result, you can use this approach to bypass the rate limiting mechanism by dividing the stream into multiple chunks, downloading them separately, and then combining them together into a single file. To do that, you will need to know the total size of the stream, which can be extracted either from the contentLength property in the metadata (if available), or from the Content-Length header in the initial response.

Below is an example of how that entire logic can be implemented using the curl command-line utility in a simple Bash script:

# Set the URL of the stream

URL='https://rr12---sn-3c27sn7d.googlevideo.com/videoplayback?...'

# Get the total size of the stream

SIZE=$(curl -I $URL | grep -i Content-Length | awk '{print $2}')

# Fetch the stream in 10 MB chunks and append the data to the output

for ((i = 0; i < $SIZE; i += 10000000)); do

curl -r $i-$((i + 9999999)) $URL >> 'output.mp4'

done

Muxing streams locally

YouTube offers a selection of different formats for each video, but you will find that the high-definition options are served exclusively through adaptive audio-only and video-only streams. And while that works out well for playback — as you can simply play both of them simultaneously — it’s not ideal when the intent is to download the video as a single file.

Ever since /get_video_info was removed, YouTube has been providing fewer muxed streams for most videos, usually limiting them to low-end options such as 144p and 360p. That means if you want to retrieve content as close to the original quality as possible, you will definitely have to rely on adaptive streams and mux them yourself.

Fortunately, this is fairly easy to do using FFmpeg, which is an open-source tool for processing multimedia files. For example, assuming you have downloaded the two streams as audio.mp4 and video.webm, you can combine them together in a file named output.mov with the following command:

$ ffmpeg -i 'audio.mp4' -i 'video.webm' 'output.mov'

Keep in mind that muxing can be a computationally expensive task, especially if it involves transcoding between different formats. Whenever possible, it’s recommended to use an output container that is compatible with the specified input streams, as that will eliminate the need to convert data, making the process much faster.

Most YouTube streams are provided in webm and mp4 formats, so if you stick to either of those containers for all inputs and outputs, you should be able to perform muxing without transcoding. To do that, add the -c copy flag to the command, instructing FFmpeg to copy the input streams directly to the output file:

$ ffmpeg -i 'audio.mp4' -i 'video.mp4' -c copy 'output.mp4'

However, if you plan to download YouTube videos for archival purposes, you will probably want to prioritize reducing the output size over the execution time. In that case, you can re-encode the data using the H.265 codec, which should result in a much more efficient compression rate:

$ ffmpeg -i 'audio.mp4' -i 'video.mp4' -c:a aac -c:v libx265 'output.mp4'

Using the above command, I was able to download and mux a 4K video, while cutting the file size by more than 50% compared to the streams that YouTube provided. If you want to improve the compression even further, you can also specify a slower encoding preset with the -preset option, but note that it will make the conversion process take significantly longer:

$ ffmpeg -i 'audio.mp4' -i 'video.mp4' -c:a aac -c:v libx265 -preset slow 'output.mp4'

Overall, FFmpeg is a very powerful tool, and it’s not limited to just muxing — you can use it to trim or resize videos, add custom metadata, inject subtitles, and perform a variety of other operations that can be useful when working with YouTube content. As a command-line application, it also lends itself extremely well to automation, making it easy to integrate as part of a larger workflow.

Summary

Even though many things have changed, downloading videos from YouTube is still possible and, in some ways, easier than before. Instead of /get_video_info, you can now retrieve metadata and stream manifests using the /youtubei/v1/player endpoint, which is part of YouTube’s new internal API.

The process of identifying and resolving streams is mostly the same as before, and workarounds such as rate bypassing are still relevant. However, signature deciphering has become less of a concern, because the vast majority of videos are now playable without it.

In general, the required steps to download a YouTube video can be outlined as follows:

- Fetch the video metadata using the

/youtubei/v1/playerendpoint, impersonating theANDROIDclient - If the video is playable:

- Extract the stream descriptors from the response

- Identify the most optimal stream and retrieve its URL

- If the video is age-restricted:

- Retrieve a valid player version from

/iframe_api - Download the player’s source code

- Reverse-engineer the signature deciphering algorithm

- Extract the signature timestamp from the source code

- Fetch the video metadata again, this time impersonating the

TVHTML5_SIMPLY_EMBEDDED_PLAYERclient - Extract the stream descriptors from the response

- Use the deciphering algorithm to recover the signatures and stream URLs

- Identify the most optimal stream and retrieve its URL

- Retrieve a valid player version from

- Download the stream in chunks using the

RangeHTTP header - If needed, use FFmpeg to mux multiple streams into a single file

If you have any questions or just want a more in-depth look at how all the pieces fit together, feel free to go through YoutubeExplode’s source code on GitHub. It’s fairly well-documented and should be a decent reference point for anyone interested in building their own YouTube downloader.

Reverse-Engineering YouTube: Revisited • Oleksii Holub Read More »